Depending upon who you read, female athletes may be as much as 11-18 times more likely to suffer a non-contact ACL injury than males. There are a multitude of theories about this. For the strength and conditioning practitioner, this usually involves a combination of poor landing technique (usually knee valgus) combined with a lack of hamstring strength.

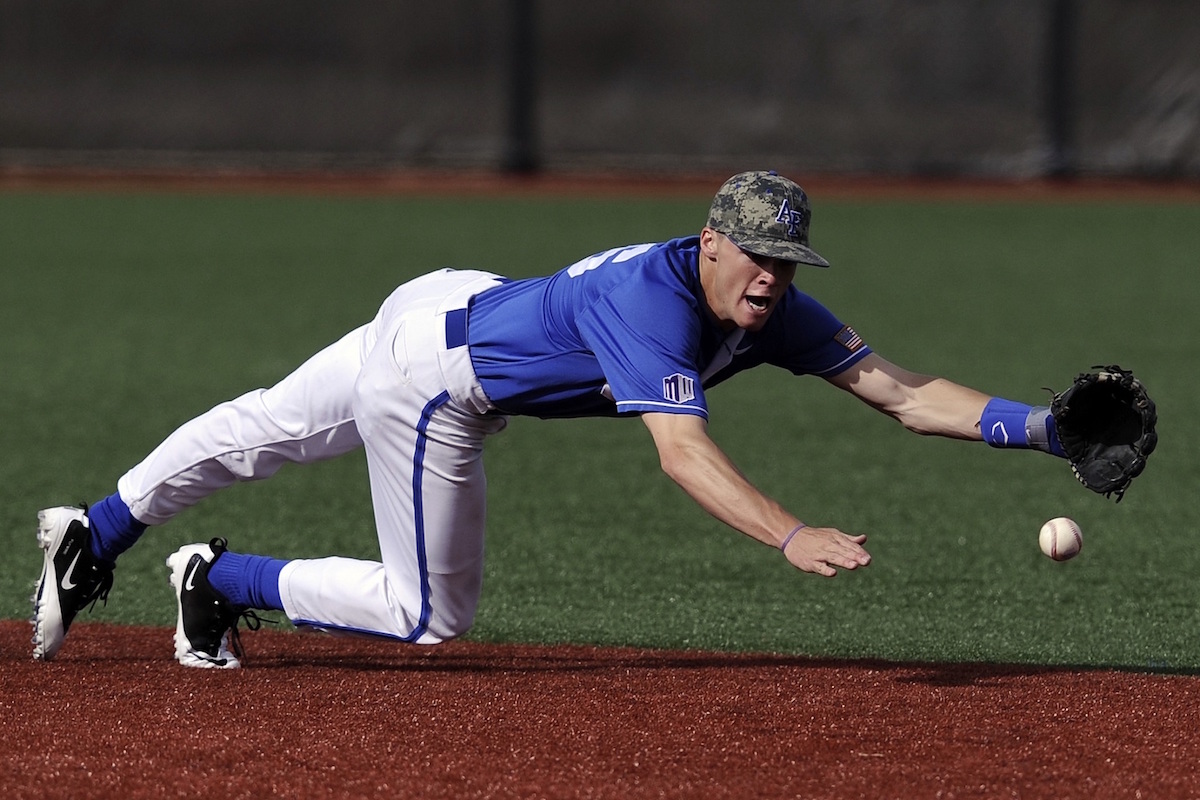

Stearns et al, in the May issue of Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, examined the relationship between knee extensor and hip extensor strength and landing biomechanics in a drop jump. In this study, 18-25 year old recreationally trained males and females had their isometric hip extensor and knee extensor strength evaluated, then were asked to perform a 36cm drop jump onto a force platform. As they landed, they were told to focus on catching a ball (focus on the ball, not on the landing) and then jump with the ball overhead. The landings were then analyzed.

The results are interesting and show differences between the genders:

• When expressed in relative terms (Nm/kg), men had almost 23% greater knee extensor strength.

• In relative terms, men had almost 33% greater hip extensor strength.

• Men achieved 15% greater knee flexion on landing

• Men achieved 10% greater hip flexion on landing.

• Females achieved 225% greater knee abduction (or valgus) on landing.

• The men’s hip extensors were 14% stronger than their knee extensors, the female hip extensors were almost 2% stronger than their knee extensors.

• Females have a 22% greater knee-hip extensor moment ratio.

This study suggests that due in part to different strength levels, the women are adopting a knee-dominated landing pattern compared to the more evenly distributed pattern of the men (i.e. distributed between the knee and the hip). It’s likely that the lack of strength is also contributing to a valgus landing strategy. All of this combined makes them more likely to suffer an ACL injury as a result of landing.

Some things should be kept in mind with this study as it has limitations. First, the individuals studied are not trained athletes. This means that, based upon these results, we cannot make sweeping statements about males and females in general. Second, it’s unclear how the focus on the ball – as opposed to landing impacted the results. By focusing on the ball, instead of landing properly, the study may have created poor landing mechanics. Third, if subjects are inexperienced at plyometrics and don’t know how to land, this will bias the results.

From the standpoint of athletics, I like this study even though it doesn’t use athletes. I like it because focusing on catching a ball while landing make this study more applicable to the real world. In most sports, when an athlete jumps and lands they are doing so to accomplish an outcome relative to the game (i.e. catch the ball, throw it, make a shot, etc.) and they are not jumping in isolation – i.e. they are distracted and not focusing on proper landing mechanics. To me, this study reinforces that a strength training program that develops the hip extensors combined with learning how to land properly is going to be extremely important to developing sound mechanics and preventing non-contact ACL injuries in female athletes.

Stearns, K.M., Keim, R.G., and Powers, C.M. (2013). Influence of relative hip and knee extensor muscle strength on landing biomechanics. Medicine and Science in Sports and Exercise, 45(5), 935-941.