The Olympic lifts and their variations are a popular tool with strength and conditioning coaches. The lifts train the entire body, involve exerting force against the ground, involve the bar moving at 2-4 meters per second, and require the athlete to generate 20-50 watts of power per kilogram of body weight (which is the highest power output of free weight exercises). Besides those reasons, these lifts teach the application of strength – in other words, they teach and individual how to express strength quickly. For all these reasons, they are used extensively in the strength and conditioning programs of athletes.

When a competitive Olympic lifter uses these lifts, he or she is trying to make the lifts as efficient as possible. What many coaches will lose sight of is that when non-Olympic lifters are using these lifts in training, it’s not necessary to make the lifts as efficient as possible because they are only being used as a means to an end rather than being the end.

Two aspects of modern Olympic lifting technique in particular can be modified when working with non-Olympic lifters to help enhance their application to other sports. The first deals with the starting position, the second deals with the second pull.

With the starting position to the Olympic lifts, it’s not unusual to see either a frog style or a low hip position in the start. Among other things, these positions allow for a “rebound” action at the start, so the lifter can get some help lifting the bar off the platform.

With regards to the second pull, many Olympic lifters are very tall with their shoulders behind the bar during the second pull. This allows for utilizing a rebending of the knees, the pull occurs more quickly, and it minimizes swinging the bar away from the body. In other words, it’s very efficient.

The photo sequence (fromhttp://nicktumminello.com/2013/01/olympic-lifting-for-athletes/) below shows a great example of what I’m describing above.

With athletes that aren’t competing in Olympic lifting, there are a few things that we want to emphasize in their strength and conditioning.

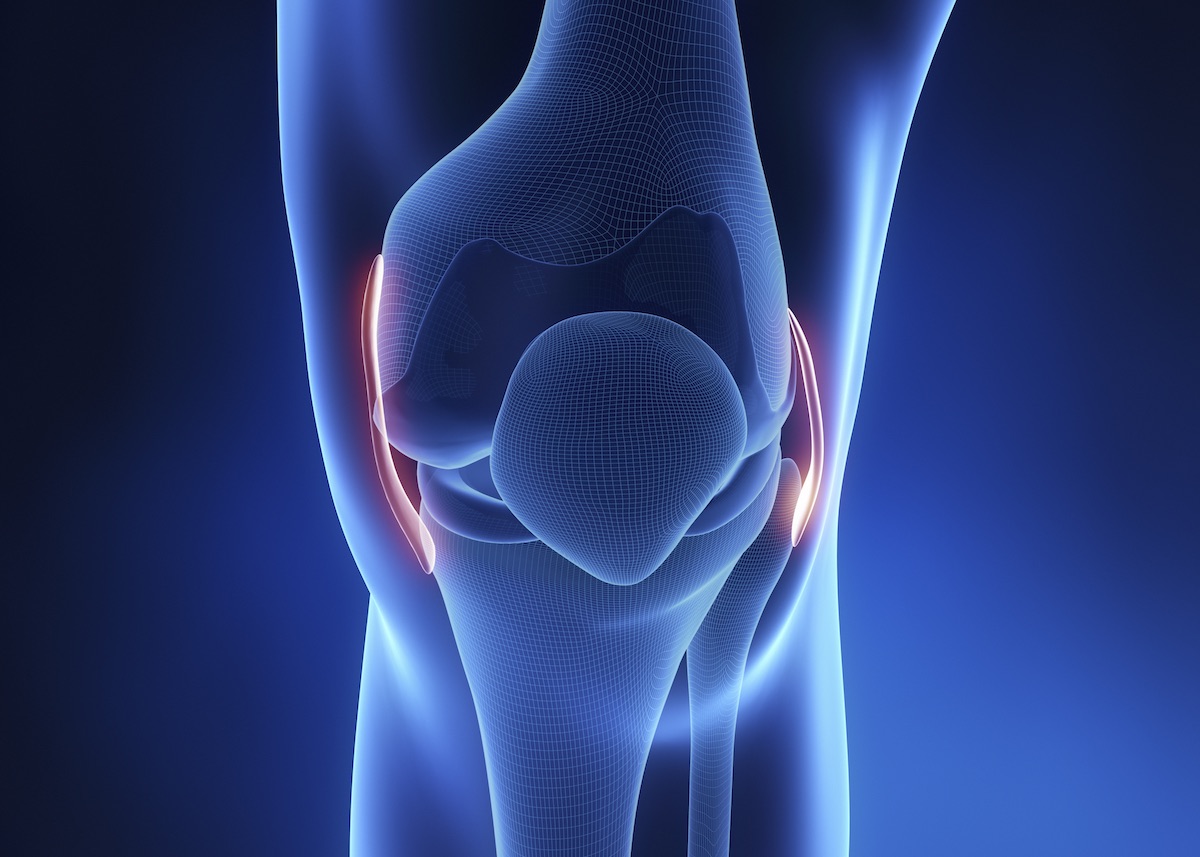

- First, we want to work on the low back/glute/hamstring connection: We use exercises that train the hamstrings in a lengthened position because it’s important for injury prevention in sprinting. We use exercises that train the muscles working together because we need that to happen to prevent knee injuries when landing.

- Second, we want to train the hip extension movement: Hip extension is important for exerting force against the ground during sprinting, jumping, and running. Hip extension is important for driving off the line of scrimmage or taking that first step explosively. It’s also key to agility movements.

To emphasize these things, I like to make Olympic lifting technique a little inefficient. I do this by making some changes to the starting position and especially to the second pull. I don’t use many lifts from the floor in training anymore, but when I use them I like to have the athlete’s hips higher and their shoulders slightly in front of the bar. Now, athlete body type dictates technique, but this reinforces the low back/glute/hamstrings working together and also emphasizes that lengthened position for the hamstrings.

With regards to the second pull, I like to focus on a longer second pull and keep the shoulders in front of the bar as long as possible. This approach will make Olympic lifting coaches cringe because it reduces the rebending of the knees, but it focuses on the hip extension and the lengthened hamstrings that I want to focus on. For me, this kind of violent hip extension comes closer to what we see in sprinting and agility movements.

Strength and conditioning is a tool for an athlete’s preparation, it’s a means to an end. This fact gives the strength and conditioning coach considerable flexibility to modify exercises or to use them creatively to accomplish their objectives.