The overload principle is a fundamental one to both training for fitness and to the strength and conditioning training of athletes. At the root of the overload principle is the fact that the body adapts to exercise. If you think about it, no matter why you are exercising or what you are doing – this is why you exercise. Your muscles get larger, this is an adaptation. Your maximal oxygen consumption improves, this is an adaptation. It’s why everyone does it.

Here’s the challenge, the body doesn’t “want” to adapt to exercise. Now I understand that the body doesn’t “want” things like a five year old wants a cookie, but it’s a useful way to explain this. Adapting to exercise is expensive. Muscle mass requires additional calories to support, extra mitochondria is expensive, etc. So the body only adapts as much as it needs to when responding to training.

This means that to continue making gains from training, one has to continually coax the body into that. This is the essence of the overload principle. Put simply it says that in order to keep making gains from exercise, you have to find a way to make it more difficult.

First we’re going to discuss some ways to achieve this, then we’ll drop the other shoe.

Regardless of the mode of exercise, there are several ways that you can apply the overload principle to a program. These include:

- Increase the volume

- Increase the intensity

- Change the rest and recovery

- Change the exercises

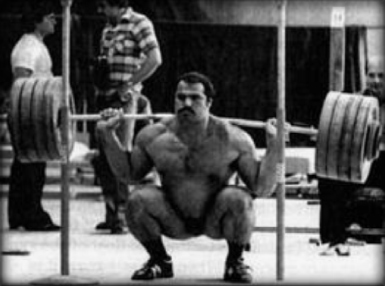

Now, each of these ways to apply the overload principle is interrelated. For example, if you increase the amount of weight on the back squat, you are going to be performing fewer repetitions and you’ll require more rest between sets.

Let’s take a minute and cover the other side of the overload principle. This principle has to be applied while keeping your goals in mind. If you are a 100 meter sprinter, you can increase the distance of your training sprints but soon you’ll be training the wrong qualities. Likewise, if you are training to improve how much weight you can bench press then sets of thirty reps would be more difficult, but they would not be improving your 1-RM on the bench press.

The other thing to keep in mind is that the closer one gets to their genetic potential, the more difficult it is to apply this principle and keep your goals in mind. As you get closer to your genetic potential it becomes more difficult to safely increase intensity or volume. This is why I like the “change the exercise” route for more advanced athletes.

- There are many exercises that train the exact same movements, muscles, and qualities. For example, we can back squat. We can also perform the following exercises and develop the lower body and trunk in a manner that involves standing on both feet and pushing against the ground:

- Front squats

- Overhead squats

- Goblet squats

- Pause squats

- Eccentric squats

- Squats with bands

- Squats with chains

You see where I’m going. For an advanced athlete, it makes sense to change training exercises every few weeks to keep them adapting – but this has to be done in a manner that keeps their goals in mind.