The immune system plays an interesting role in exercise, recovery, and adaptations from exercise. In an article I read years ago I had read that delayed onset muscle soreness (that soreness we get 24-48 hours post-exercise) tracks well with the timeline for the immune system response to that exercise session. In other words, we might become sore from exercise due to the fact that the immune system is attacking/repairing the damage that we did.

Peake et al had an excellent review article in the Journal of Applied Physiology on the immune system and exercise. The authors divided their paper into several parts:

- Leukocytes and exercise

- Repeated exercise bouts/prolonged intense training

- Nutritional interventions

Before I get into the paper, I think it’s important to talk, big picture, about how the immune system functions. It has been a long time since I had a general physiology course and this is something that is not covered well in exercise physiology, so I had to go back and look at Guyton’s excellent physiology textbook to review.

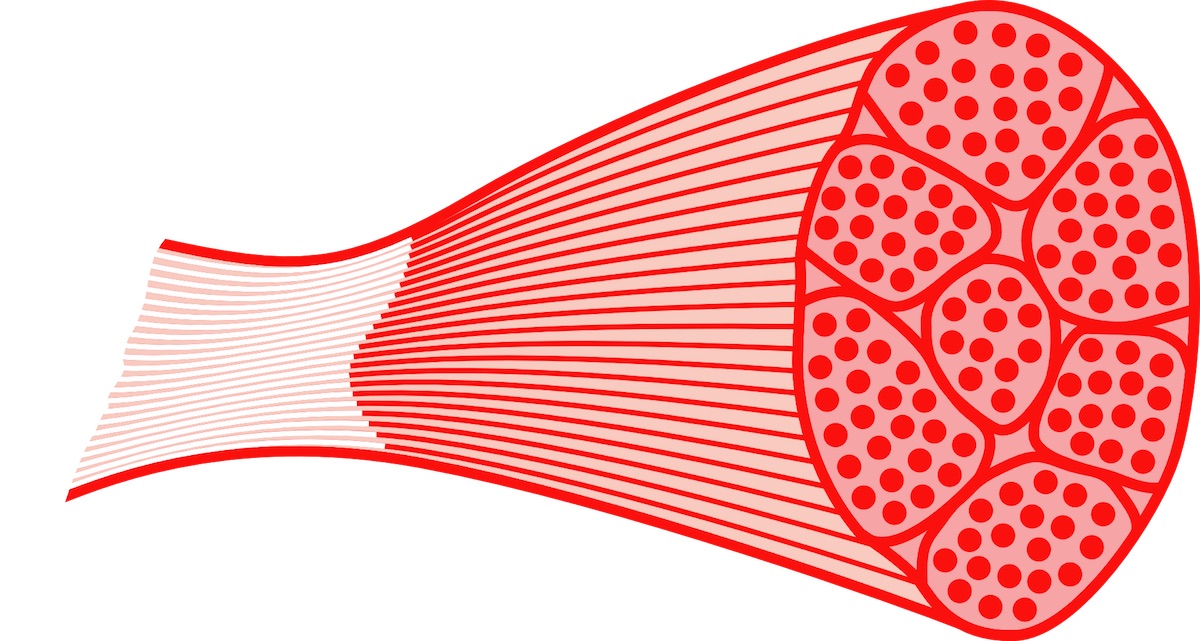

Basically, the body treats exercise as an infection. Because of that, there are white blood cells (also known as leukocytes) involved in the recovery process. There are six types of leukocytes: polymorphonuclear neutrophils, polymorphonuclear eosinophils, polymorphonuclear basophils, monocytes, lymphocytes, and occasionally plasma cells. The polymorphonuclear cells have more than one nucleus. They, along with monocytes, protect the body against invading organisms by eating them (also known as phagocytosis). These types of cells are also produced in the bone marrow.

White blood cells are attracted to inflammation. Basically, when a tissue is inflamed it produces chemicals that attract the white blood cells to it.

Inflammation is interesting and important with regards to our response to exercise. Inflammation is caused by tissue injury. According to Guyton (p. 397), a number of things occur during inflammation:

- Vasodilation to the local blood vessels

- Increased capillary permeability, means that fluids can leak outside the damaged cells

- Local clotting

- Migration of large numbers of polymorphonuclear cells and monocytes into the tissue

- Macrophages begin phagocytosis within minutes of the start of inflammation

- Within the first hour, neutrophils begin to enter the inflamed area.

- Monocytes begin to enter the inflamed area. This takes several days to become effective because monocyctes are not stored in circulating blood.

- Finally, more of the polymorphonuclear cells and monocytes are produced from bone marrow.

- Swelling of the tissue

There is also another part of the immune system that deals with immunity. These are driven by lymphocytes, which come from the lymphatic system. This includes T cells and antibodies (aka immunoglobulins).

With that review, let’s look at the article.

Leukocytes and exercise:

A single bout of exercise sees an increase in leukocytes during the exercise. Neutrophils continue to increase for several hours post exercise. Monocytes are mobilized and infiltrate skeletal muscle to facilitate repair.

However, this all changes during prolonged, exhausting exercise. When this happens the immune system is depressed and this continues for several hours. This suggests why athletes that are in the middle of very intense blocks of training, long seasons, and that are overtrained are susceptible to illness and injury.

Repeated exercise bouts/extended periods of intense training:

What if we exercise more than once a day? How about several weeks of overreaching? The authors found the following:

- With aerobic exercise, two sessions a day resulted in a higher amount of total leukocytes and neotrophils following the second bout.

- Overreaching leads to a suppression of leukocytes.

Nutrition and immune function:

The authors reviewed the literature on how nutrition impacts the immune system after exercise. They found that:

- Carbohydrate supplementation before and during exercise may reduce the number of leukocytes both during exercise and for several hours of recovery.

- High carbohydrate diets (~8-9 g/kg/day) reduce overreaching symptoms during periods of intense training.

- High protein diets (3 g/kg/day) also have a positive impact on the immune system’s response to exercise

So, some take home information from this review for the coach:

- Carbohydrates are important to athletes.

- Protein is also important.

- If athletes are getting sick during training phases it’s a good indication that they aren’t able to recover from the training and that suggests that training needs to be scaled back. Better to have the athletes healthy and contributing that slavishly sticking to the plan and wrecking them.

References:

Guyton, A.C. and Hall, J.E. (2000). Textbook of Medical Physiology, 10th Edition. W.B. Saunders Company: Philadelphia, 392-400.

Peake, J.M., Neubauer, O., Walsh, N.P., and Simpson, R.J. (2017). Recovery of the immune system after exercise. Journal of Applied Physiology, 122: 1077-1087.

1 thought on “Immune System and Exercise: Recovery and Diet Really Are Important”

Comments are closed.