“Train for what you want”

This is one of the most fundamental principles in strength and conditioning and it’s the one that everyone overthinks and makes too complicated. For most of us, this is really simple. If you want to improve on something then you have to practice the thing you want to improve on. Failing to do this means that you are relying on chance to make improvements, which is not a good idea for a competitive athlete or a coach.

In many ways, this really is pretty simple. If you want to improve your speed, you have to practice running fast in training. If you want to improve your squat, you have to do squats in training. If you want to improve your vertical jump, you need to practice the jump. Now, in each of these examples there are other exercises and modes that can help you, but it all boils down to practicing what you want to improve.

Think about it. If you want to improve your free throw percentage in basketball, do you focus on dribbling and hope that this will somehow improve your free throws? It is the same thing and it is this simple for most athletes.

Wait a minute, lots of athletes make this more complicated, don’t they? Elite powerlifters are focusing on exercises that train parts of the bench press, squat, and deadlift that have sticking points. Elite weightlifters are training parts of the snatch, clean, and jerk to work on their deficiencies. Elite sprinters and jumpers are doing complex drills to work on aspects of their event.

There’s an important word in all of the above examples, elite. Elite athletes have needs that are totally different from the rest of us. First of all, realize that elite athletes have been at their craft for a long time. This means that many of them have the base that the rest of us are struggling to develop. Second, elite athletes have made as many gains as they can training like the rest of us and they are at the point where focusing on the minutiae is the only way they will make improvements. Finally, realize that at the elite level fractions of a second or a few pounds makes a huge difference between winning and not even placing. For other categories of athletes, these can be distracting and take away from finite training time that could be focused on other things.

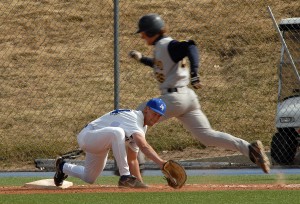

Below is an example of distractions paired with examples of how to fix them. The example here is speed training to help a high school baseball player run to first base more quickly. First, we have an example of overcomplicating the training:

Fence kick drill, 2×10 on each leg

Bounds, 3×10 yards

A walks, 3×10 yards

A skips, 3×10 yards

Standing starts, 3×60 yards

Crouching starts, 3×60 yards

Now, on the surface this is a fine speed development workout. With the fence kick, bounds, and A drills we progress through the parts of the sprinting motion – eventually tying it all together. The standing and crouching starts allow us to work through more explosive starts to help achieve a higher maximum velocity on the runs. The distances are such that we’ll work on maximum velocity development. So what’s wrong with this?

The problem is we’re training a baseball player to move from hitting a baseball to sprinting 30 yards to first base. First they won’t reach maximum velocity. This means the A drills and the 60 yard drills won’t be helpful. Second, they will not start the sprints from a standing or crouching start, so this is training them for something they won’t actually do in their sport.

Below is an example of a workout that prepares them to be better at running to first base:

High knee walks, 3×10 yards

Bounds, 3×10 yards

First step batting drill, 5-10x

Batting stance sprints, 3-5×35 yards

The high knee walks and bounds are specific to the kind of acceleration running this athlete will be doing on the way to first base. Bounds are also a great drill to train horizontal force application. The athlete needs to learn how to move from swinging the baseball bat and hitting the ball to being prepared to start sprinting, so the first step drill practices that motion (this is a drill that practices only the transition from hitting to sprinting, there is no running with this drill). Lastly, we go from batting stance to the swing to sprinting 35 yards which will take the athlete slightly beyond first base (we’re training them to run through the base).

Overthinking training can actually severely restrict the gains from training. Everyone wants to put their stamp on things, I get that. Everyone wants to look really smart, cutting edge, and creative. I get that too. But, sometimes in our rush to look smart we overthink things to the point where they don’t work as well as keeping things simple.