Speed is an important skill in most sports. We all write volumes about it, go to clinics to pick up new drills and movement cues, and seek out speed training gurus. Our athletes are evaluated on it and it’s a major focus of their training. Here’s the thing, outside of track and field most athletes need to be able to decelerate and stop on a dime to transition into doing something else.

I coach baseball and basketball. In both sports the ability to decelerate is critical. In baseball, my baserunners can’t run through second and third base, there are times they have to run very fast to those bases to avoid the throw but they have to be able to stop on the base. In basketball, we never get to run in a straight line as fast as we want, the court has fixed distances and the game has defenders who want to take the ball from us and stop us from doing what we want.

With that in mind, this blog will talk about decelerating and being able to transition into other movements. I’m going to keep this pretty generic and foundational, you can use this and make it sport-specific to met your needs. The rest of this blog will cover things we can do in team sport situations to develop the ability to decelerate, stop, and move on to another skill.

First, we need lower body strength. I know, this is my solution to just about everything. Strength is important for speed, it makes sense that it is also important for stopping under control. This means squats, hip hinges, lunges, split squats, deadlifts, and variations of the Olympic lifts.

Second, we need speed. I’ve done a lot of writing about this one so I’m going to avoid writing a lot about this.

Third, we need good reaction time, especially in the context of the sport. I say this because our athletes have to be able to suddenly stop and do something else based upon what happens during the game. I’m going to argue that reaction time is going to be a really specific skill.

For example, understanding that a pitcher is throwing a 70 mph change up instead of the 90 mph fast ball is different than reading the defense in basketball to understand that you are about to be trapped in the corner by two defenders and need to pass the ball before that happens. This is very hard for a strength and conditioning coach to work on using cone drills and it’s why some agility training needs to be in the context of the sport and it’s why we need to partner with our sport coaches.

Now, we can train reaction time in the weight room. For example, we might execute explosive lifts to an outside cue. Instead of just doing a set of four power cleans, we might have the athlete lift the bar as explosively as possible after a tone sounds, or after they are touched, or after someone shouts go. You see where I’m going here.

Fourth, we can start to teach the ability to decelerate and perform a different skill using cone drills. I don’t have anything against cone drills, my issue is when we rely on them 100% after they have outlived their usefulness. Two good drills that begin to teach this skill are the “M” drill and a drill that involves moving two cones up and one cone back.

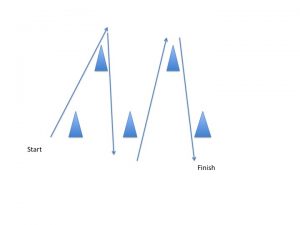

M Drill:

Set the cones up in an “M” (see illustration below). Make them as far apart or as wide apart as you want, depends on what qualities you want to train. Have the athlete run from the start (by the first cone) up to the second. From here they need to stop and backpedal (or defensive slide, or shuffle, or turn and run) to the third cone. Stop, run forward to the fourth cone. Stop, and move to the fifth cone and the finish line.

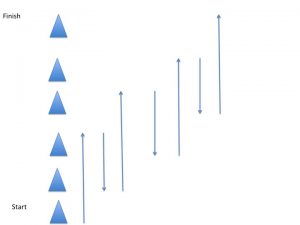

Two up one back drill:

Set the cones up in a line. Make them as far apart as you want and put as many as you want (but at least 5-6). The athlete starts at the start line and then sprints forward two cones. Then they stop and backpedal (or defensive slide, or shuffle, or turn and sprint) one cone. Sprint forward two more cones, then move back one. Repeat until they cross the finish line.

These are examples of drills that teach how to decelerate and stop. Once your athletes have this down, we move to putting this into sport contexts.